WORDS

The Bul-Tigs

January 31, 2021I started writing this over 3 years ago. It was just a few days after the parkland high school shooting had happened in Parkland, Florida where 17 people were killed, and 17 others were injured. We were only a few months removed from the “unite the right'' rally in Charlottsvile that had left one person dead from a white supremicist driving their car through a crowd of anti protesters. We were barely a year into 45’s presidency, but I could tell things were getting worse by the day. I always give my parents a call to get their perspective and words of assurance when times are looking bleak. Growing up in rural South Carolina for their entire lives they’ve seen and witnessed a lot of things that I cannot have imagined. I decided to call them that day, and record the conversation so I could write about it.

They were teenagers during the civil rights and black power movement in the 60s and early 70s. At the time I was thinking we were heading in a direction where the country might be more like their teenage years, and I wanted to know more about what that was like. Really, I only had to listen to the popular music of their senior year of high school to get a picture of what the country was like. There were plenty of anti war songs, women empowerment, and black power movement songs. No song summarized it better than The Temptations’ ‘ball of confusion’ that was released in 1970. With lyrics like “Segregation, determination, demonstration, integration, aggravation, humiliation, obligation to our nation”, and “the cities ablaze in the summertime”, this song could have easily been just as relevant today.

I’ve heard plenty of stories from them, but not many of the details. They’ve kept all of their year books from high school, and there has always been a few I’ve skimmed through. My mom’s senior yearbook had odd colors that weren’t the school colors, but I just assumed the colors themselves had faded over the years so I never really asked about it. Schools first started integrating in the US in 1954. South Carolina where my parents grew up, was one of the last places to integrate. The assassinations of Malcom X, MLK, and Fred Hampton had all happened within 5 years of each other leading up to their senior year of high school in 1970. In my mind I would have thought that year of school for them would have been one of the toughest, but as I found out it wasn’t vastly different from any of the others. I’m sure the fact that integration already happening virtually everywhere else in the country made things a little less tense. What follows here are their stories, perspectives, and experiences of growing up in a time that was so vastly different than ours, but in so many ways still all too similar.

my parents late 70s

Braxton: I always remember this one story that dad used to tell me. Y'all were on a bus, going to school or coming from school and the bus caught on fire or crashed and people were driving by saying all types of crazy stuff.

Mom: That was me.

Braxton: Was that you? What was going on?

Mom: Our bus turned over on it’s side, and people drove by in trucks going bring more Niggers next time. It was a long time before I wanted to ride a school bus after that. It was a rainy crazy day, and we were going down dirt roads, and it turned over on the dirt roads. He went around the curve too fast.

Braxton: Who were you on the bus with? Were you on it with any of your brothers and sisters?

Mom: Yeah, Tommy was probably on there. Fred was probably on there. We were just going to elementary school one morning, and at that time the bus drivers were high school students. They were young.

Braxton: They were high school students? Were they black or were they white?

Mom: They were black.

Braxton: Oh yeah because all the schools weren't integrated were they?

Mom: Right. They weren't integrated. We were in elementary school. It was somewhere down like on the St. Paul roads back down through the country roads, and it was Kenny Earl Anderson. He drove around a corner too fast, or a curve too fast and the bus turned over, and they had to pull us up through the windows on the bus and some of the, you know, white people came by saying bring more Niggers the next time. And I mean it just didn't help, it was crazy.

Braxton: Did you go to school after that or did you go home?

Mom: I'm sure they took us all to check us out, but I'm sure we came home after that. We didn't go to school that day.

Braxton: Well let me backtrack a little bit. Was that the first time that you remember having something like that happen, or really encountered some crazy racism mom?

Mom: No, when I was little, and our mama took Franklin and I to nye's drugs to get some ice cream and our aunt she tried to put us up on the counter and she cursed a few people out that day. Its a wonder we didn't go to jail, but we didn't. That was my first bout. Another time we went to Brookgreen gardens on a school trip and they had colored and white bathrooms, and the colored bathrooms were broken and they wouldn't let us go in the white bathrooms. That was miserable. I mean, Oh man. It's just so much.

Braxton: What about you dad?

Dad: No, my first encounter, I was elementary school age, and it wasn't really racism and the fact that I knew that was different between, you know, black and white where you had to go at it was a doctor's office, and first of all, the black people had to go in the back and go to a different side of side of the office, you know, you couldn't sit where the white patients were. So actually, you know that was my first, and walking downtown and seeing like colored and white on the water fountains. Just knowing that's not for us kind of stuff. Then far as actually hearing anything, probably we were little playing in the yard and the buses came by, you know, and the kids and they would yell out nigger, just stuff like that. But actually as a child growing up, I didn't really encounter a lot of just firsthand, you know, racism this kind of stuff. It was just more kept separate. You know, because you know where to go and where not to go. So we didn't go on the side of town where we know all the white people were that sort of thing. Just stayed basically in our communities really.

Braxton: That's the other thing you know, both of you went to school with white people for like how many years? Not that many....

Mom: One year. My junior year I was a liaison between Whittemore High and Conway high.

Braxton: So you were in charge of making sure the transition went smoothly essentially?

Mom: Not In charge but I was on the committee. Yes.

Braxton: What kind of stuff would y'all do to make it a smooth transition.

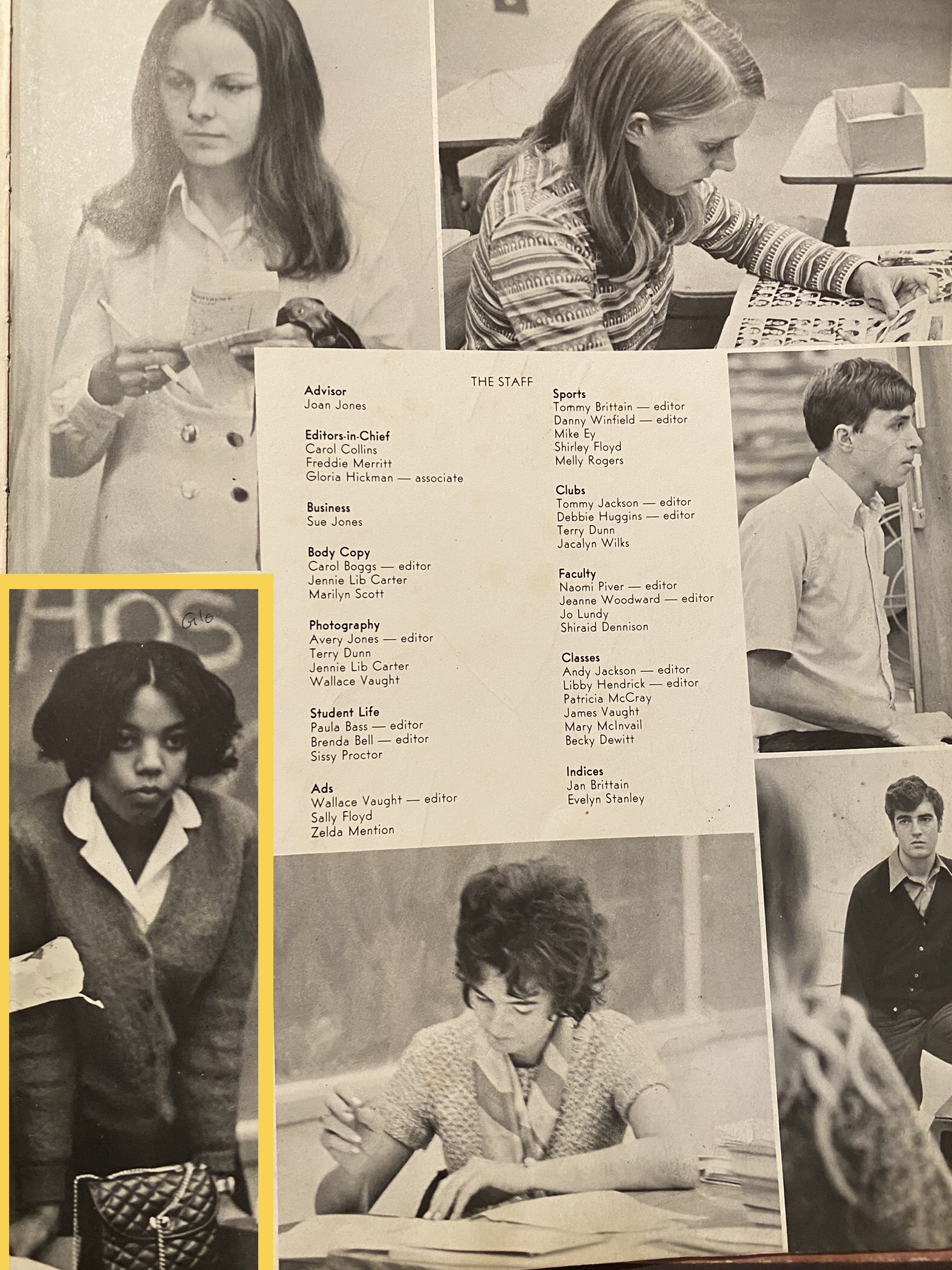

Dad: Well I know one thing they created like a club called the bull-tigs. That was all the black and white people that wanted to come together and form this or whatever. Just to help.

Braxton: It was called the What?

Dad: The Bul-Tigs, like Bulldogs and Tigers (the mascots from each segragated school)

![Bul-Tigs Club 1970]()

![Bul-Tigs club member]()

Braxton: Oh, okay.

Dad: Yeah

Mom: Yeah. But we did things like, we looked at how we were gonna combine the colors because whittemore (all black school) was purple and gold, and Conway (all white school) was orange and green at the time.

Braxton: oh. So that's how they came up with Green and Gold?

Mom: Yeah.

Braxton: Oh wow. So you were on the committee. Wait, wait, so you were on the committee that actually created my high school colors.

Mom: Yep

![]()

(mom pictured bottom left)

Braxton: That's crazy.

Mom: Yep That's crazy. And then if you look at our yearbook that year, we made our yearbook purple and orange because those are the two colors we didn't use. We met about once a month. We did a lot, and a lot of the stuff came through our community and from both schools. So the transition wasn't really that bad.

![Yearbook cover for first integrate year]()

(mom’s senior yearbook)

Dad: It wasn't really bad for me because I never got in a fight, never had any altercations, and I made friends in the class. I mean just I didn't have a problem at all.

![]()

Braxton: Yeah. Well I was going to say what was the first year like? You've been going to school with black people for 15 or let's see for 10 to 11 years. Do you remember the first day? Do you remember what it was like? Were you nervous?

Mom: I mean I don’t remember the first day of school, I think because I had been to Conway high so many times before it wasn't that bad, but I do remember, I remember my senior year. It wasn't bad because they kind of separated you into your own? I would have been in the honors track. And so I was in a student council home room so I was in with the leaders from every grade level.

![]()

Dad: Yeah. Just, you know, you just met people there. I played baseball and basketball. I didn't play football at Conway High, but I played baseball and basketball. I met people through sports I guess.

Mom: I would say there were 270 in my high school, I think there were 70 black kids that came to Conway high because Whittemore first maybe had Myrtle Beach, Socastee Area all of them came.

Dad: I remember it's kind of like you go to school, you know, you go to school, and all of sudden there's just some white people in the classes. It was easy to me, it wasn't really a problem at all.

Braxton: I just think it would be so weird. It's weird hearing you say that It was just so easy cause I feel like I, I guess I don't know what I would've been like, but I feel like It wouldn't have been easy.

Dad: I think it depends on what kind of person you are too because a lot of people, a lot of black people, you know just rejected going over there, you know, they went to pick fights and just didn't want to integrate. I figured that was what we had to do so it was just easier to accept it than reject it, you know, but I think I had seen some fights. People got in fights and stuff, you know, because somebody called them nigger or something and then that was a fight.

Braxton: That didn't happen everyday? I just imagine that just happening every day.

Mom: Yeah? I didn't think it would happen a lot.

Dad: Back then it was kind of like the MLK people, and the Malcom X black people. Well, whenever they met man, you know, it was just like, something was gonna happen, and didn't nobody want to give in.

Mom: Your uncle Franklin got put out for fighting back then.

Dad: Yep.

Mom: Franklin got put out for fighting that first year they integrated. He lasted till about December I believe. But that was before we went. He went in 1969 and then he got put out for the rest of the year. And then he went back to Whittemore in 1970 and graduated.

Mom: Yeah, that was an interesting time. But I honestly enjoyed my senior year of high school. I've had a lot of white friends and black friends and still do.

Dad: Right, and there were some white kids that would always hang with us.

Mom: Yeah, and there was always that one, you know, that really thought that should have been, you know, just with y'all, at the time that you did not even think about whether they white or black.

Braxton: Well, I think the difference now is that I would imagine back then it was so obvious the differences, not even the differences, but I think it was just much more obvious of the advantages and disadvantages that you probably faced from being black and white and now is not as much. So now people think that you are equal or whatever, and it's probably just as divided.

Mom: And you know what I was trying to explain that the other day and it's because we kind of got complacent in it and you come up and you just ignore it, you know or Oh that's just a little off. But then now I know Trump has given everybody permission to come out of the closet. It's just crazy.

Dad: Yeah. You'll see more hate and stuff since he came into the picture, and all these old hicks come back out and just all these hate crimes and stuff.

Mom: And then you see somebody you thought, you know how in the world could they think like that? I mean,a lot of things come with a Trump thought.

Dad: See I always thought being prejudiced just didn’t make sense. You see somebody is black and just automatically think something about them. That was just always mind boggling to me. I mean how can you be, how do you hate somebody, and be mean to them and you didn't know anything about them, didn't even know their names.Sounds crazy.

Braxton: Yeah,

Dad: That was the way the world was geared from slavery until now.

Braxton: I always had a lot of white friends growing up. I feel like if I would've went through a quarter of the stuff that y'all went through.... I mean watching me grow up, were you ever like you should have more black friends or kind of how your mom was saying be careful.

Dad: You mean far as for you?

Braxton: Me or Tia (sister)? Yeah, both of us. I guess.

Mom: You didn't have a lot of people, a lot of choices your age so I wasn't even worried about what color your friends were. I was more concerned that your friends were friends.

Dad: I was more worried about them being a bad influence, that was the most important thing, I didn't care if they were white or black, I didn't want you to be in a bad environment.

Mom: And you weren’t, you were doing fine, but I felt bad. I wish I had this letter that you wrote to me a long time ago, and I cannot find it, you described how it felt to be pulled between two worlds. I knew you were going through it. But I figured, if you were happy where you were wasn't my choice and no, and you know, even when y'all were little I never even talked about black and white. We just talked about people around you, but behind your back we probably talked about it, you know, we just tried to keep y'all out of it.

Braxton: Well whenever we went to the African American History Museum, we would be walking and then there would be a Paul Laurence Dunbar thing and then I'd be like, Oh, I remember reading about him and those books. Who taught you that or like how did you come up reading that? I didn't really know and I didn't know anything, I just didn't know anything about anything really. You were always just like read this, memorize this. I think this was an important type of thing so I realized it meant something to you obviously.

Mom: Mama taught us a lot of poems and I learned, I didn't necessarily learn those poems thinking necessarily about Langston Hughes or Paul Laurence Dunbar. Those poems were kind of passed down to us through the black church.

Dad: I was more fascinated with the people, like the peanut guy, the guy that made all the stuff from the Peanuts.

Braxton: George Washington Carver.

Dad: Right. You know, I was fascinated with him. I mean he was a smart black man and he just took peanuts and made all this stuff from it. You know? I thought that was amazing. You know? He was my hero in the sense, well, when the first black heroes that you know, that was famous.

Mom: I remember being in a play in second grade and I was Phyliss Wheatley, and I had to tell a poem. It was a poem about Phillis Wheatley and at the end of the poem I had to say who am I and the kids in the audience, I know this was only the second grade and the kids and all that were trying to guess who you are that is and said I know who you are, you're Eddie Hickman! See back then we just laughed. We've had like as long as I can remember

Dad: I don't know what year the song I'm black and I'm proud came out by James Brown. But I'll tell you what, that song had impact on everybody black, I can tell you that. Just to hear that you know the song, you know, Hey, I'm, you know, I'm black and proud that song was big.

Braxton: That was 1968.

Dad: I would have been a 9th grader.

Braxton: So you were 14, 13 or 14 I guess.

Dad: And then Martin Luther King, you know, to me, he was the person that was gonna save the black people, Martin Luther King, you know, he was the guy. He wasn't afraid to speak out and you know, he had a big impact. He was kind of like our God in a sense. That's the way I saw him anyway.

Mom: Well a lot of it came through the black church and prior to the black church. We were in an all black school.

Mom: Yeah, but at some point a solution has to come. But out of every time it's the young people who make a difference. So this, that little group of people in Florida [parkland students] might be the key.

Dad: Yeah it seems like they were speaking way beyond their years. I don't know if they were coached to that or what.

Mom: And that was that same group of young people who did the civil rights movement too. Those people who kind of came of age at a time when they could make differences. That's the only thing that's going to change something is voting. So I believe this is going to be a different one here.

Check out the Bul-Tigs music mix on the vibes page here.

Mom: That was me.

Braxton: Was that you? What was going on?

Mom: Our bus turned over on it’s side, and people drove by in trucks going bring more Niggers next time. It was a long time before I wanted to ride a school bus after that. It was a rainy crazy day, and we were going down dirt roads, and it turned over on the dirt roads. He went around the curve too fast.

Braxton: Who were you on the bus with? Were you on it with any of your brothers and sisters?

Mom: Yeah, Tommy was probably on there. Fred was probably on there. We were just going to elementary school one morning, and at that time the bus drivers were high school students. They were young.

Braxton: They were high school students? Were they black or were they white?

Mom: They were black.

Braxton: Oh yeah because all the schools weren't integrated were they?

Mom: Right. They weren't integrated. We were in elementary school. It was somewhere down like on the St. Paul roads back down through the country roads, and it was Kenny Earl Anderson. He drove around a corner too fast, or a curve too fast and the bus turned over, and they had to pull us up through the windows on the bus and some of the, you know, white people came by saying bring more Niggers the next time. And I mean it just didn't help, it was crazy.

Braxton: Did you go to school after that or did you go home?

Mom: I'm sure they took us all to check us out, but I'm sure we came home after that. We didn't go to school that day.

Braxton: Well let me backtrack a little bit. Was that the first time that you remember having something like that happen, or really encountered some crazy racism mom?

Mom: No, when I was little, and our mama took Franklin and I to nye's drugs to get some ice cream and our aunt she tried to put us up on the counter and she cursed a few people out that day. Its a wonder we didn't go to jail, but we didn't. That was my first bout. Another time we went to Brookgreen gardens on a school trip and they had colored and white bathrooms, and the colored bathrooms were broken and they wouldn't let us go in the white bathrooms. That was miserable. I mean, Oh man. It's just so much.

Braxton: What about you dad?

Dad: No, my first encounter, I was elementary school age, and it wasn't really racism and the fact that I knew that was different between, you know, black and white where you had to go at it was a doctor's office, and first of all, the black people had to go in the back and go to a different side of side of the office, you know, you couldn't sit where the white patients were. So actually, you know that was my first, and walking downtown and seeing like colored and white on the water fountains. Just knowing that's not for us kind of stuff. Then far as actually hearing anything, probably we were little playing in the yard and the buses came by, you know, and the kids and they would yell out nigger, just stuff like that. But actually as a child growing up, I didn't really encounter a lot of just firsthand, you know, racism this kind of stuff. It was just more kept separate. You know, because you know where to go and where not to go. So we didn't go on the side of town where we know all the white people were that sort of thing. Just stayed basically in our communities really.

Braxton: That's the other thing you know, both of you went to school with white people for like how many years? Not that many....

Mom: One year. My junior year I was a liaison between Whittemore High and Conway high.

Braxton: So you were in charge of making sure the transition went smoothly essentially?

Mom: Not In charge but I was on the committee. Yes.

Braxton: What kind of stuff would y'all do to make it a smooth transition.

Dad: Well I know one thing they created like a club called the bull-tigs. That was all the black and white people that wanted to come together and form this or whatever. Just to help.

Braxton: It was called the What?

Dad: The Bul-Tigs, like Bulldogs and Tigers (the mascots from each segragated school)

Braxton: Oh, okay.

Dad: Yeah

Mom: Yeah. But we did things like, we looked at how we were gonna combine the colors because whittemore (all black school) was purple and gold, and Conway (all white school) was orange and green at the time.

Braxton: oh. So that's how they came up with Green and Gold?

Mom: Yeah.

Braxton: Oh wow. So you were on the committee. Wait, wait, so you were on the committee that actually created my high school colors.

Mom: Yep

(mom pictured bottom left)

Braxton: That's crazy.

Mom: Yep That's crazy. And then if you look at our yearbook that year, we made our yearbook purple and orange because those are the two colors we didn't use. We met about once a month. We did a lot, and a lot of the stuff came through our community and from both schools. So the transition wasn't really that bad.

(mom’s senior yearbook)

Dad: It wasn't really bad for me because I never got in a fight, never had any altercations, and I made friends in the class. I mean just I didn't have a problem at all.

Braxton: Yeah. Well I was going to say what was the first year like? You've been going to school with black people for 15 or let's see for 10 to 11 years. Do you remember the first day? Do you remember what it was like? Were you nervous?

Mom: I mean I don’t remember the first day of school, I think because I had been to Conway high so many times before it wasn't that bad, but I do remember, I remember my senior year. It wasn't bad because they kind of separated you into your own? I would have been in the honors track. And so I was in a student council home room so I was in with the leaders from every grade level.

Dad: Yeah. Just, you know, you just met people there. I played baseball and basketball. I didn't play football at Conway High, but I played baseball and basketball. I met people through sports I guess.

Mom: I would say there were 270 in my high school, I think there were 70 black kids that came to Conway high because Whittemore first maybe had Myrtle Beach, Socastee Area all of them came.

Dad: I remember it's kind of like you go to school, you know, you go to school, and all of sudden there's just some white people in the classes. It was easy to me, it wasn't really a problem at all.

Braxton: I just think it would be so weird. It's weird hearing you say that It was just so easy cause I feel like I, I guess I don't know what I would've been like, but I feel like It wouldn't have been easy.

Dad: I think it depends on what kind of person you are too because a lot of people, a lot of black people, you know just rejected going over there, you know, they went to pick fights and just didn't want to integrate. I figured that was what we had to do so it was just easier to accept it than reject it, you know, but I think I had seen some fights. People got in fights and stuff, you know, because somebody called them nigger or something and then that was a fight.

Braxton: That didn't happen everyday? I just imagine that just happening every day.

Mom: Yeah? I didn't think it would happen a lot.

Dad: Back then it was kind of like the MLK people, and the Malcom X black people. Well, whenever they met man, you know, it was just like, something was gonna happen, and didn't nobody want to give in.

Mom: Your uncle Franklin got put out for fighting back then.

Dad: Yep.

Mom: Franklin got put out for fighting that first year they integrated. He lasted till about December I believe. But that was before we went. He went in 1969 and then he got put out for the rest of the year. And then he went back to Whittemore in 1970 and graduated.

Mom: Yeah, that was an interesting time. But I honestly enjoyed my senior year of high school. I've had a lot of white friends and black friends and still do.

Dad: Right, and there were some white kids that would always hang with us.

Mom: Yeah, and there was always that one, you know, that really thought that should have been, you know, just with y'all, at the time that you did not even think about whether they white or black.

Braxton: Well, I think the difference now is that I would imagine back then it was so obvious the differences, not even the differences, but I think it was just much more obvious of the advantages and disadvantages that you probably faced from being black and white and now is not as much. So now people think that you are equal or whatever, and it's probably just as divided.

Mom: And you know what I was trying to explain that the other day and it's because we kind of got complacent in it and you come up and you just ignore it, you know or Oh that's just a little off. But then now I know Trump has given everybody permission to come out of the closet. It's just crazy.

Dad: Yeah. You'll see more hate and stuff since he came into the picture, and all these old hicks come back out and just all these hate crimes and stuff.

Mom: And then you see somebody you thought, you know how in the world could they think like that? I mean,a lot of things come with a Trump thought.

Dad: See I always thought being prejudiced just didn’t make sense. You see somebody is black and just automatically think something about them. That was just always mind boggling to me. I mean how can you be, how do you hate somebody, and be mean to them and you didn't know anything about them, didn't even know their names.Sounds crazy.

Braxton: Yeah,

Dad: That was the way the world was geared from slavery until now.

Braxton: I always had a lot of white friends growing up. I feel like if I would've went through a quarter of the stuff that y'all went through.... I mean watching me grow up, were you ever like you should have more black friends or kind of how your mom was saying be careful.

Dad: You mean far as for you?

Braxton: Me or Tia (sister)? Yeah, both of us. I guess.

Mom: You didn't have a lot of people, a lot of choices your age so I wasn't even worried about what color your friends were. I was more concerned that your friends were friends.

Dad: I was more worried about them being a bad influence, that was the most important thing, I didn't care if they were white or black, I didn't want you to be in a bad environment.

Mom: And you weren’t, you were doing fine, but I felt bad. I wish I had this letter that you wrote to me a long time ago, and I cannot find it, you described how it felt to be pulled between two worlds. I knew you were going through it. But I figured, if you were happy where you were wasn't my choice and no, and you know, even when y'all were little I never even talked about black and white. We just talked about people around you, but behind your back we probably talked about it, you know, we just tried to keep y'all out of it.

Braxton: Well whenever we went to the African American History Museum, we would be walking and then there would be a Paul Laurence Dunbar thing and then I'd be like, Oh, I remember reading about him and those books. Who taught you that or like how did you come up reading that? I didn't really know and I didn't know anything, I just didn't know anything about anything really. You were always just like read this, memorize this. I think this was an important type of thing so I realized it meant something to you obviously.

Mom: Mama taught us a lot of poems and I learned, I didn't necessarily learn those poems thinking necessarily about Langston Hughes or Paul Laurence Dunbar. Those poems were kind of passed down to us through the black church.

Dad: I was more fascinated with the people, like the peanut guy, the guy that made all the stuff from the Peanuts.

Braxton: George Washington Carver.

Dad: Right. You know, I was fascinated with him. I mean he was a smart black man and he just took peanuts and made all this stuff from it. You know? I thought that was amazing. You know? He was my hero in the sense, well, when the first black heroes that you know, that was famous.

Mom: I remember being in a play in second grade and I was Phyliss Wheatley, and I had to tell a poem. It was a poem about Phillis Wheatley and at the end of the poem I had to say who am I and the kids in the audience, I know this was only the second grade and the kids and all that were trying to guess who you are that is and said I know who you are, you're Eddie Hickman! See back then we just laughed. We've had like as long as I can remember

Dad: I don't know what year the song I'm black and I'm proud came out by James Brown. But I'll tell you what, that song had impact on everybody black, I can tell you that. Just to hear that you know the song, you know, Hey, I'm, you know, I'm black and proud that song was big.

Braxton: That was 1968.

Dad: I would have been a 9th grader.

Braxton: So you were 14, 13 or 14 I guess.

Dad: And then Martin Luther King, you know, to me, he was the person that was gonna save the black people, Martin Luther King, you know, he was the guy. He wasn't afraid to speak out and you know, he had a big impact. He was kind of like our God in a sense. That's the way I saw him anyway.

Mom: Well a lot of it came through the black church and prior to the black church. We were in an all black school.

Mom: Yeah, but at some point a solution has to come. But out of every time it's the young people who make a difference. So this, that little group of people in Florida [parkland students] might be the key.

Dad: Yeah it seems like they were speaking way beyond their years. I don't know if they were coached to that or what.

Mom: And that was that same group of young people who did the civil rights movement too. Those people who kind of came of age at a time when they could make differences. That's the only thing that's going to change something is voting. So I believe this is going to be a different one here.

Check out the Bul-Tigs music mix on the vibes page here.